Low Energy Landing

Keep it Safe

A low energy landing is desired to ensure a controlled stop within the available landing distance at Harris Hill. The upwind wing should be low if there is a crosswind. The upwind wing should be the wing that is gently flown to the ground as glider comes to a stop.

Low energy means that excess speed is dissipated. The tail should be lower than normal flight attitude. On most glider types this should approximate a two-point landing with the main wheel and tailwheel touching at the same time. (The Schweizer 2-33 is one notable exception.) The pitch attitude should be fixed prior to touchdown.

To avoid carrying unwanted approach speed into the landing zone a good pilot uses the base leg to adjust altitude (potential energy) and turns final within the effective range of the dive brakes (the approach wedge.) The dive brakes then dissipate energy in the form of drag while the selected approach airspeed is maintained. It is not desirable to pitch down to get down, allowing the airspeed to build. If a forward slip is used it important to use good technique to not gain or lose airspeed in the slip.

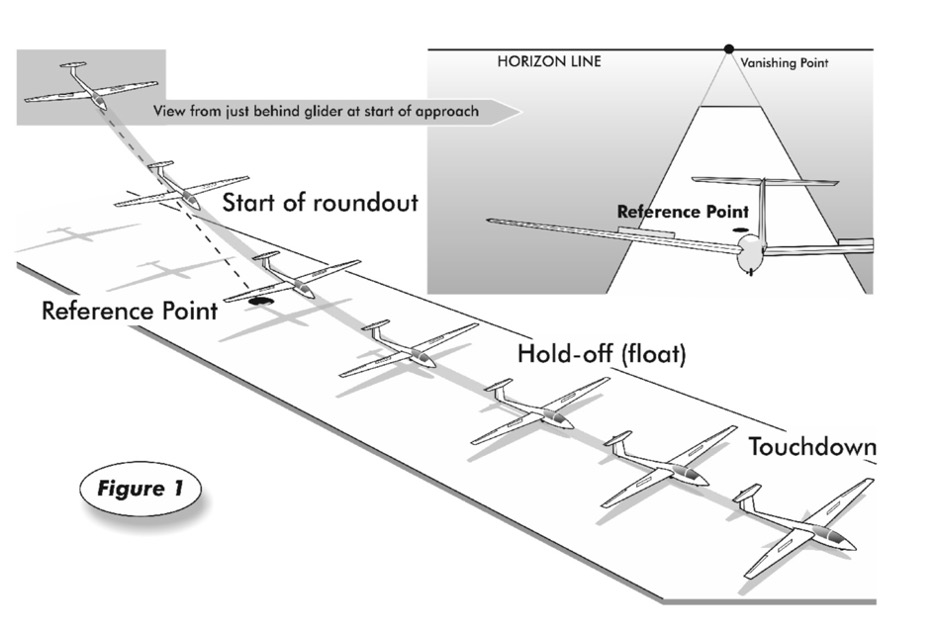

Every knot of approach airspeed added above the low energy touchdown speed must be lost in the round-out and flare. While the reference point in pattern planning can aptly be described as the landing zone, once established on final the pilot should pick a more precise reference point short of the desired touchdown point. He or she should allow more distance for the round-out and the flare proportional to any extra approach speed carried. This step is essential for precise landings needed at Harris Hill.

The selected touchdown point should be easily inside the boundary of the airfield. Aircraft landing north have struck the tailwheel on the brow of the hill on the south end of the airport on multiple occasions. Landing south all manner of uphill landings have been attempted due to poor planning and fixation with having to land on top of the hill.

The round-out and the flare should be thought of as two separate maneuvers. Each requires a bit of time and distance to achieve properly.

For the round-out, the pilot continues the final approach on a downward trajectory until the main wheel is within approximately one half a wingspan of the ground. Timing the round-out varies somewhat by aircraft type. Some gliders have stubby wings; others have high aspect ratio and will have more ground effect. Entering the round-out, the pilot transitions from looking at the reference point to looking at the far end of the runway while changing pitch to smoothly achieve a decreasing descent rate and ultimately arresting the descent with the main wheel approximately 3 feet from the ground.

Avoid opening fully closed dive brakes close to the ground. The dive brakes or spoilers should be smoothly positioned somewhere between 1/2 and 2/3 travel prior to round-out. Occasionally, full dive brakes may be the way to go. The wheel brake should not be engaged while airborne. Hold the spoiler handle steady through the round-out and flare as a general rule.

Although the term flare seems to imply an all-at-once operation, it too takes place over time and distance. The more approach speed carried into ground effect, the more deliberate the pilot must be to not climb during the flare. After dissipating extra speed, the pilot raises the nose, without climbing, to the desired pitch attitude and holds that attitude to allow the glider to settle into the landing.

The ground roll should be kept straight until everything is under control and taxi speed is achieved. Only then can gentle taxi maneuvers be used to clear the landing zone for gliders behind.